As the audience sat, enraptured and shocked, watching the first preview of climate-thriller Kyoto in London, 5500 miles away in Los Angeles, the planet was literally on fire.

It’s a haunting parallel that underscores the urgency and gravity of this new play. Kyoto is a story where the stakes could never be higher: the future of our species is on the line.

Premiering in Stratford-upon-Avon last summer, Kyoto, the gripping new production from the RSC and Good Chance Theatre, has transferred to the West End—and not a moment too soon. The play captures the origins of the climate crisis as it unfolded on the world stage, charting the behind-the-scenes battles to create the first global agreement on climate change. Yet, in light of recent events, it plays less like a history lesson and more like a horror story. Simply put, this is theatre at its most prescient.

Prescience isn’t uncharted territory for the remarkable Good Chance theatre company. Founded by Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson a decade ago, they burst onto the global stage with their groundbreaking 2017 production, The Jungle. That play was politically charged and deeply human, portraying real-life stories of loss, fear, resilience, and hope among refugees living in a migrant camp in Calais. Directed by Stephen Daldry and Justin Martin, it immersed audiences in a wraparound design that placed them directly—and often uncomfortably—in the heart of the action.

Now, reuniting that same extraordinary creative team for the first time, Kyoto feels cut from the same cloth. It is equally political, immersive, and fiercely timely, forcing its audience to reckon with the systems and power structures that shape our world – and our future.

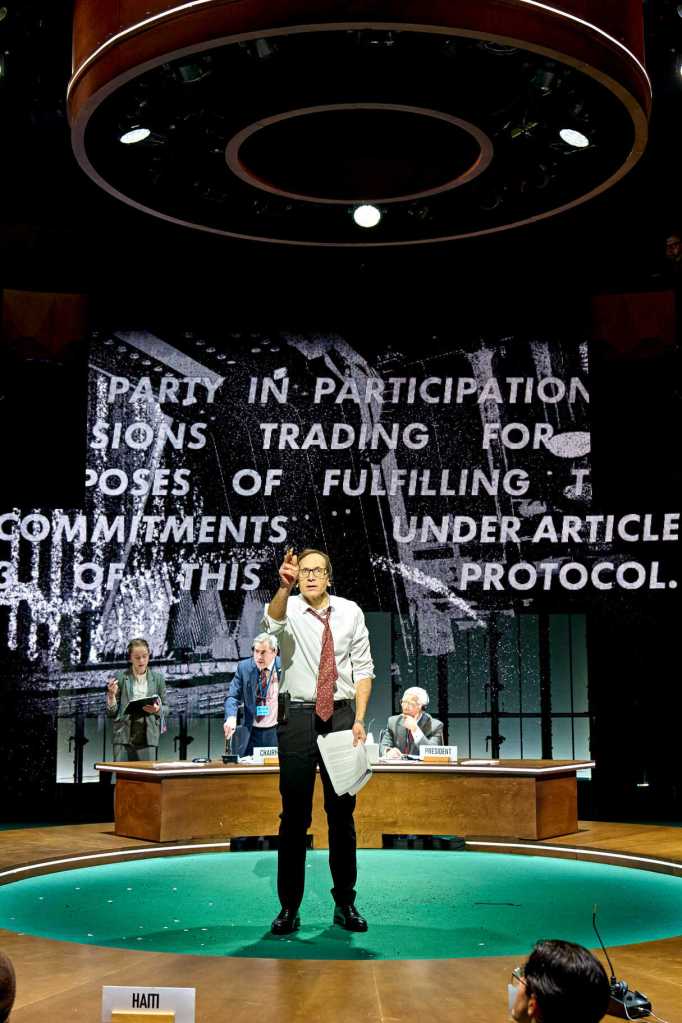

The immersive power of Good Chance is again realised in Kyoto, with much of the drama unfolding in various conference rooms around the globe. This makes it a snug fit for @sohoplace, the West End’s newest and most modern theatre, which carries its own “conference-y” atmosphere. Miriam Buether’s set design centres the action around a large UN-style roundtable positioned in the middle of the room, with the play’s delegates seated among the audience. Adding to the immersion, patrons are handed lanyards upon arrival, blurring the line between spectator and participant.

However, I must confess, it would have been fascinating to see Kyoto staged in the Elizabethan-style Swan Theatre at the RSC. This is largely because Joe Murphy and Joe Robertson have crafted a play that feels genuinely Shakespearean in both style and scope.

At its core, Kyoto is a history play: most of the characters are symbolically named after locations, and the use of asides and direct address draws the audience directly into the action. It even wears its Shakespearean influences on its sleeve. One particularly memorable moment in act one recreates a surreal production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, directed by Werner Herzog and staged in the Amazon Rainforest, to coincide with the 1992 Rio Earth Summit.

And at it’s heart lies a truly Shakespearean villain. It’s a bold choice by the theatremakers to centre the play around Don Pearlman, a real-life Wall Street lawyer and oil lobbyist who becomes an insidious force within the climate talks. When he first steps on stage—wiry-thin, clad in a shabby suit, and hidden behind spectacles—he exudes the unassuming demeanour of a “grey man.” But it doesn’t take long to realise this is a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Grey men like Pearlman, from corporate lobbyists to bureaucratic masterminds, operate in the shadows, pulling strings while maintaining plausible deniability. They are dangerous not because they demand attention but because they avoid it, manipulating systems and outcomes with chilling efficiency.

American actor Stephen Kunken delivers a masterful performance as Pearlman, playing him with brilliant malice and electrifying energy. His portrayal is highly intellectual, razor-sharp, and deeply menacing. Slipping into the shadowy corners of the climate negotiations, Kunken embodies the invisible hand driving the play’s conflict. Like all great villains, he’s also genuinely funny, his cutting quips and observations adding a layer of charisma that makes his character all the more compelling.

There are shades of Othello’s Iago in Pearlman, as he manipulates the action, sowing discord for personal gain, driven by self-interest and a mastery of psychological warfare. Likewise, there’s a bit of Richard III in his willingness to dismantle everything in his path for power and profit, a ruthlessness masked by charm and intelligence.

Thankfully for our planet, Pearlman faces a formidable adversary in Raúl Estrada, brought to life with humour and warmth by Jorge Bosch. As an Argentine diplomat and lawyer who eventually becomes Chair of the Kyoto Summit, Estrada is the perfect counterpoint to Pearlman’s ruthless cunning. Bosch’s performance is both disarming and commanding, offering a moral centre to the play that balances Pearlman’s cold, calculated manoeuvres.

Their dynamic lies at the heart of Kyoto. Pearlman embodies an “America first” ideology. The Jewish son of Lithuanian immigrants who rose from humble beginnings to the halls of the White House. Pearlman mistakes the history of America as the history of the world. His air of American exceptionalism shapes his worldview: everything is binary—it’s about winning or losing, and he will do whatever it takes to win.

In contrast, Estrada champions compromise. For him, diplomacy is about setting aside differences and prioritising collective interests over individual gain. His approach to the Kyoto talks reflects his belief in unity and shared responsibility, making him the ideal foil to Pearlman’s unyielding, zero-sum tactics. The tension between these two ideologies—the hard pragmatism of profit versus the fragile hope of collaboration—drives the emotional and political stakes of the play, making the climax all the more extraordinary.

For a play about policy, politics, protocols and even punctation – Kyoto is remarkably entertaining and utterly watchable. The playwrights treat their dense, complex source material as a political thriller, weaving a globe-trotting narrative of behind the scenes power play. The script is cinematic in its pacing, and the action takes place at breakneck speed, pulling the audience along. You get the impression it will make for excellent screen material one day.

That said, my one critique lies with the portrayal of the “Seven Sisters,” the powerful oil companies Pearlman serves. They are depicted as cult-like figures, shrouded in dark hoods with ominous music underscoring their scenes. While this is undoubtedly a theatrical choice, the effect feels cartoonish. These entities would have been far more chilling—and realistic—if they were presented as they truly are: corporate executives in tailored suits, haunting the negotiations with quiet menace.

The play doesn’t shy away from uncomfortable truths, including a sly aside near the end that references the oil industry’s insidious infiltration of the arts. Even the RSC, one of the play’s collaborators, faced criticism over its controversial partnership with BP, which funded its £5 ticket scheme for young people. It’s a sharp, meta moment that reminds us how deeply entrenched these industries are in our cultural and political fabric. “It always finds a way in,” one character says. “What does?” asks Pearlman. “Oil.”

Pearlman, as flawed and malicious as he is, isn’t entirely wrong. He delivers a cutting line: “Saving the world is filthy business.” The play holds the United Nations to account, highlighting the hypocrisy of delegates flying to Kyoto and generating significant carbon emissions to discuss reducing them. And did those talks succeed? As the famous cherry blossoms in Kyoto bloom earlier with each passing year, the answer remains painfully ambiguous.

As Kyoto depicts, the greatest challenge that science ultimately faces is communication—translating its warnings, data, and urgency into something that can inspire action. This is where Kyoto proves vital. It takes an overwhelming, systemic issue and transforms it into a gripping and human narrative, forcing its audience to confront not just the failures of the past but the insidious structures that continue to shape our future.

Kyoto is both a warning and a reminder of what’s at stake. For all its moments of humour and theatricality, it leaves an indelible impression. In a week where Los Angeles burns and climate deniers regain power on the global stage, the play’s message couldn’t be clearer: the time to act is not tomorrow or next year. It is now.

Kyoto runs at @sohoplace until 3rd May, 2025. Tickets are available here.

Photo Credits: Manuel Harlan and The RSC.